- Sample:

- 6f8f1b26324ea0f3f566fbdcb4a61eb92d054ccf0300c52b3549c774056b8f02 (Bazaar, VT, AnyRun)

- Infection chain:

- Excel -> mshta downloader -> x86 injector -> x86 injector -> Dridex first stage

- Difficulty:

- Intermediate

The downloader

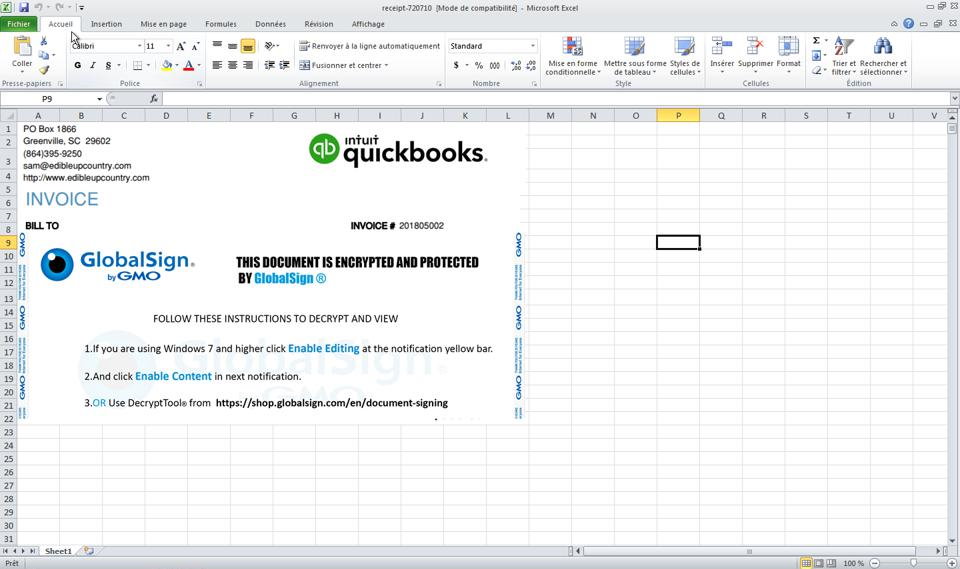

Excel document

The sample we are going to dissect came as a 728KB Excel 97 document inside an email. The OLE container is pretty simple: most of its space is taken by the Excel Workbook (711KB). The rest is made of metadatas (claim to be Invoice 720710 from Quickbooks, LLC) and a small VBA project. A legit-looking picture from GlobalSign on the first Excel sheet tells the user to enable editing + content in order to decrypt the office document. This manipulation will indeed enable and run the document (malicious) macros.

The VBA project contains a single WorkBook_Open macro. In Excel, the WorkBook_Open macro is automatically run when the document is opened. By hitting F4 in Malcat, we can decompile the VBA code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

The macro is pretty straightforward, and write the content of the sheet cells from A65 up to O2886 into a file, before running the file through the mshta.exe program. As we already suspected given the size of the Workbook stream, it means that the payload is actually stored inside the sheet cells.

Malcat can parse both Biff8 (.xls) and Biff12 (.xlsb) Excel binary documents. Just double-click on the Workbook stream in the Virtual File System tab of the OLE container and you can inspect the content of the excel document. To display cell values and (decompiled) formulas, you can hit F4. This time there is no formula inside the sheet, but a lot of numerical values inside the cells lies in the ascii range, which is kind of unusual.

Extracting the Mshta Downloader

The cells are displayed in order in the decompiler view, so it should be easy to recover the written file programmatically. We can do it two ways:

- Copy-paste the content of the F4 view (starting at the cell

$B$65) into an editor and post-process it using python or your text editor of choice macros. - Use Malcat's scripting to iterate over the cell values and reconstruct the file.

We will choose the second solution. Using Malcat's script engine, we have access to the file format parser and its result in the malcat.analyzer variable. In this case, the Biff8 file format parser (in data/filetypes/Office.Workbook8.py) stores some extra cell information in its sheets variable. Go to the script editor view via F8 and enter the following script:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

We obtain the following HTML file (comments have been removed for clarity):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 | |

The Mshta script listed above is a pretty straightforward downloader. Let's just try to WGET one of the url:

1 2 3 4 | |

Hmm no luck. But maybe they do User-Agent filtering. Let's use the user agent provided in the script:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Bingo, we have the file!

The first stage

Locating the payload

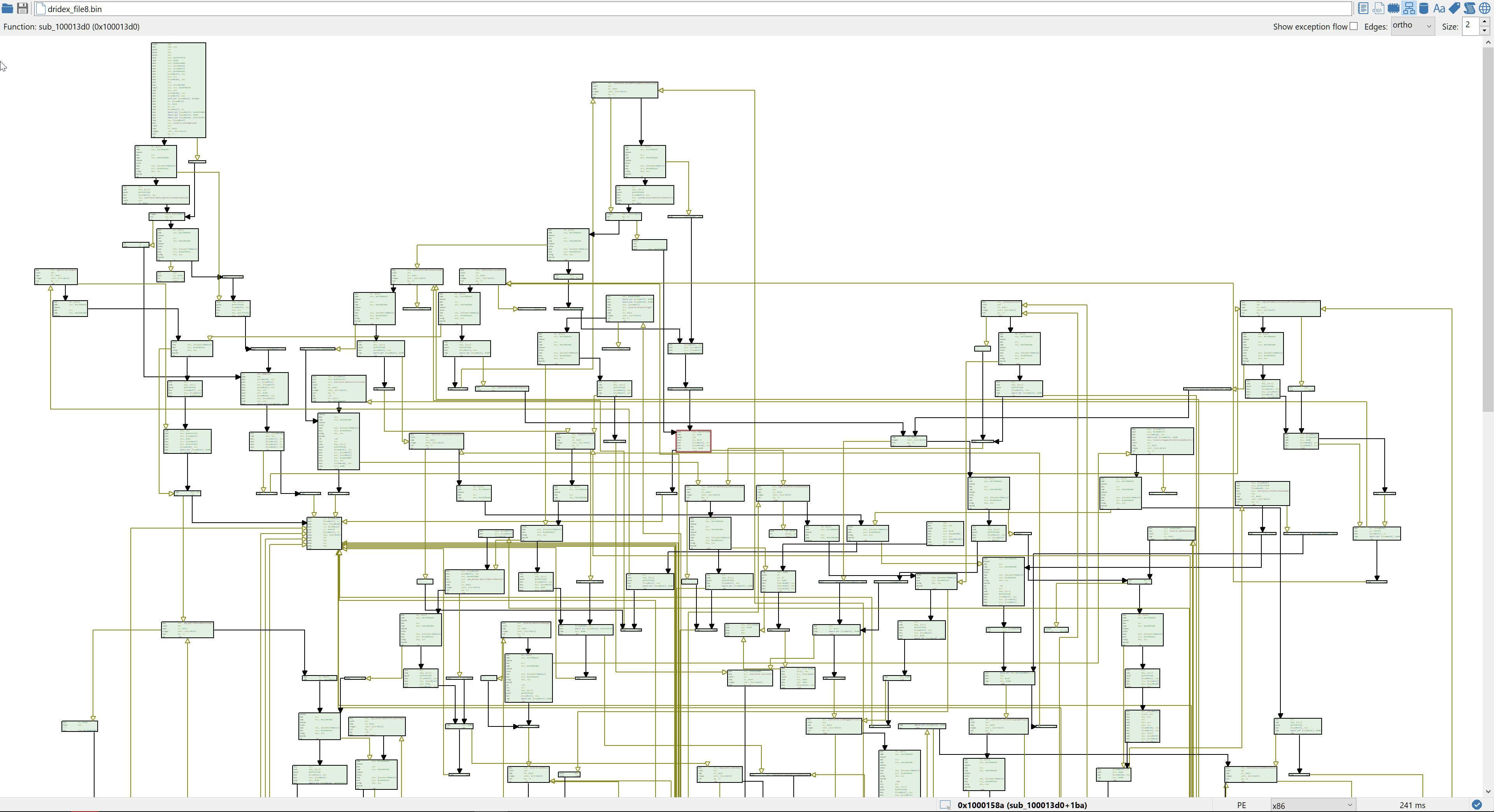

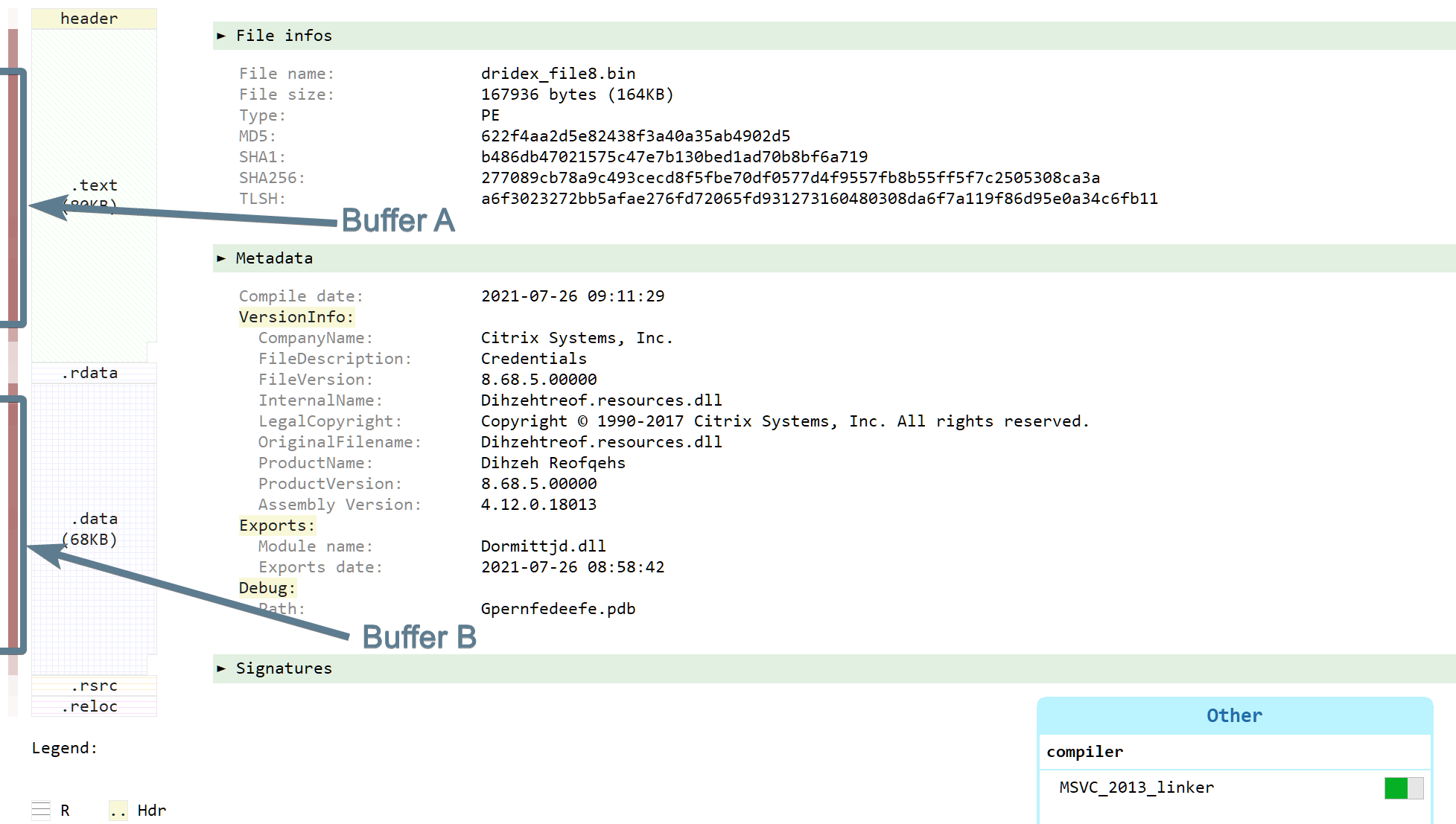

The downloaded file is a 167KB PE file of sha256 277089cb78a9c493cecd8f5fbe70df0577d4f9557fb8b55ff5f7c2505308ca3a (Bazaar, VT, AnyRun) and plays in a higher league. We don't know much about the file since both the version informations and the rich header seem fake. And while the number of identified functions seems low (55), most of them seem obfuscated. How to be sure they are obfuscated? Well there are a lot of fake API calls, a lot of useless arithmetic operations, and the control flow graph (F4) of some of the functions look like this:

While I enjoy pure static analysis, this would be the point where I would normally switch to dynamic analysis. Reversing obfuscated code is not really fun. But on the other hand, dealing with anti-VM and anti-debugging tricks is also not very fun. So let's give static analysis a chance. Since looking at the code there won't bring us much, we will first do the usual preliminary work: locating the payload data. We have two high-entropy buffers there:

- one in the .text section at approximatively

0x10002a8d-0x10012ab8(about 0x1002b bytes): this will be buffer A - one in the .data section at approximatively

0x1001619f-0x10026265(about 0x100c6 bytes): this will be buffer B

This definitely looks like payload material. Then we will look for cross-references to these two buffers (right-click on the first byte in data view, and choose cross-references).

There is exactly one cross-reference for each of these buffers:

- one cross-reference to buffer A in the .data section at address

0x10026264. The pointer itself is not referenced. - one cross-reference to buffer B in the .data section at address

0x10026200. The pointer is itself referenced by the functionsub_10013940at address0x100139f4

The first buffer looks like a dead-end, let us have a look at the second, and more particularly to the function sub_10013940.

Reversing the decryption function

Like the rest of the code, this function is obfuscated and code is bloated with arithmetic operations. But decompilers are notably good at one thing: constant propagation. So let us run the Sleigh decompiler (double-press F4) and have a look at the decompiled code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 | |

I know that the abstract of this blog post promised very few reverse engineering, but it is time to plug in our brain for a few seconds and have a quick look at the decompiled code:

- the two loops each loops twice. Two is also the number of our buffers...

iStack52in the first do-while loop is the sum of ([0x100261e8]-[0x100261a4]) =0x10000and ([0x100261e8 + 100]-[0x100261a4 + 100]) =0x10000, which could be the sizes of our two buffersiVar1seems to points to a buffer of sizeiStack52sub_10013b50, once decompiled, looks like a simple memcpy- during the first loop turn of the second do-while, the memcpy call copies

[0x10026200](our buffer B reference, see above) toiVar1,iVar2seems to be the size of buffer B (0x10000) - during the second loop turn of the second do-while, the memcpy call copies

[0x10026200 + 100]=[0x10026264](which is actually our buffer A reference, see above) toiVar1+0x10000

So without reversing further, we can roughly infer that:

- buffer B and buffer A are actually both 0x10000 bytes big

- our two buffers are concatenated into the iVar1 buffer (buffer B followed by buffer A)

- function

sub_100136f0gets called on the result

So that wasn't too much complicated until now. Now let's have a look at sub_100136f0:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

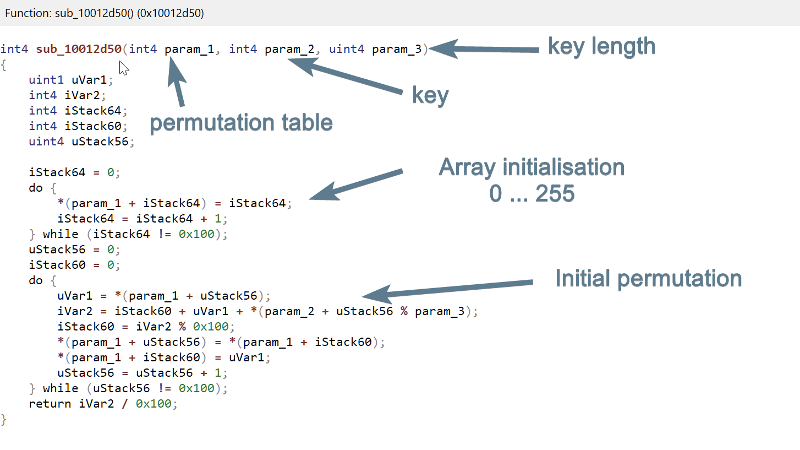

Looks like this function calls two sub-functions which both use a 256 bytes buffer internally (axStack272). The first function sub_10012d50 takes as parameters the 256 bytes buffer, a pointer to some high-entropy data (at 0x10015161) and the integer 0x3b. If we looks at the decompiled code of sub_10012d50, it should ring some bells for malware analysts:

We see indeed a first loop which initialises a 256 bytes buffer with values from 0 to 255, and a second loop which permutes some of the cells of the buffer. It looks a lot like a RC4 initialisation function. So instead of reversing further, we will first verify if our hypothesis holds. We will append 0x20000 bytes to the end of the file, concatenate buffer B and buffer A in this overlay and try to decrypt the two buffers using Malcat's RC4 transform and the 0x3b bytes key at 0x10015161 (small tip: first open a copy of the program with 0x20000 additional bytes at the end of the file to make room for the concatenated buffers):

It works! Well, kind of at least. This definitely looks like a PE file, but parts of the MZ and PE headers are still encrypted. This is a common anti-dump trick used to confuse signature-based memory dumpers. The first 32 bytes of the result (all set to zero) also seems useless, which would explain the line *(param_1 + 4) = iVar1 + 0x20; in function sub_10013940.

Reconstructing the headers

Obviously, some other function in the program is responsible for fixing the MZ and PE headers of the decrypted buffer. So, we should navigate through the obfuscated code and locate it right? But since the PE header seems to be only partially encrypted (the string "This program cannot be run in DOS mode" is still visible as well as section names), we could try to be smarter and save some time. Let us diff the decrypted buffer with another valid PE, for instance the first layer (chances are they have been generated using the same compiler, which makes the job easier).

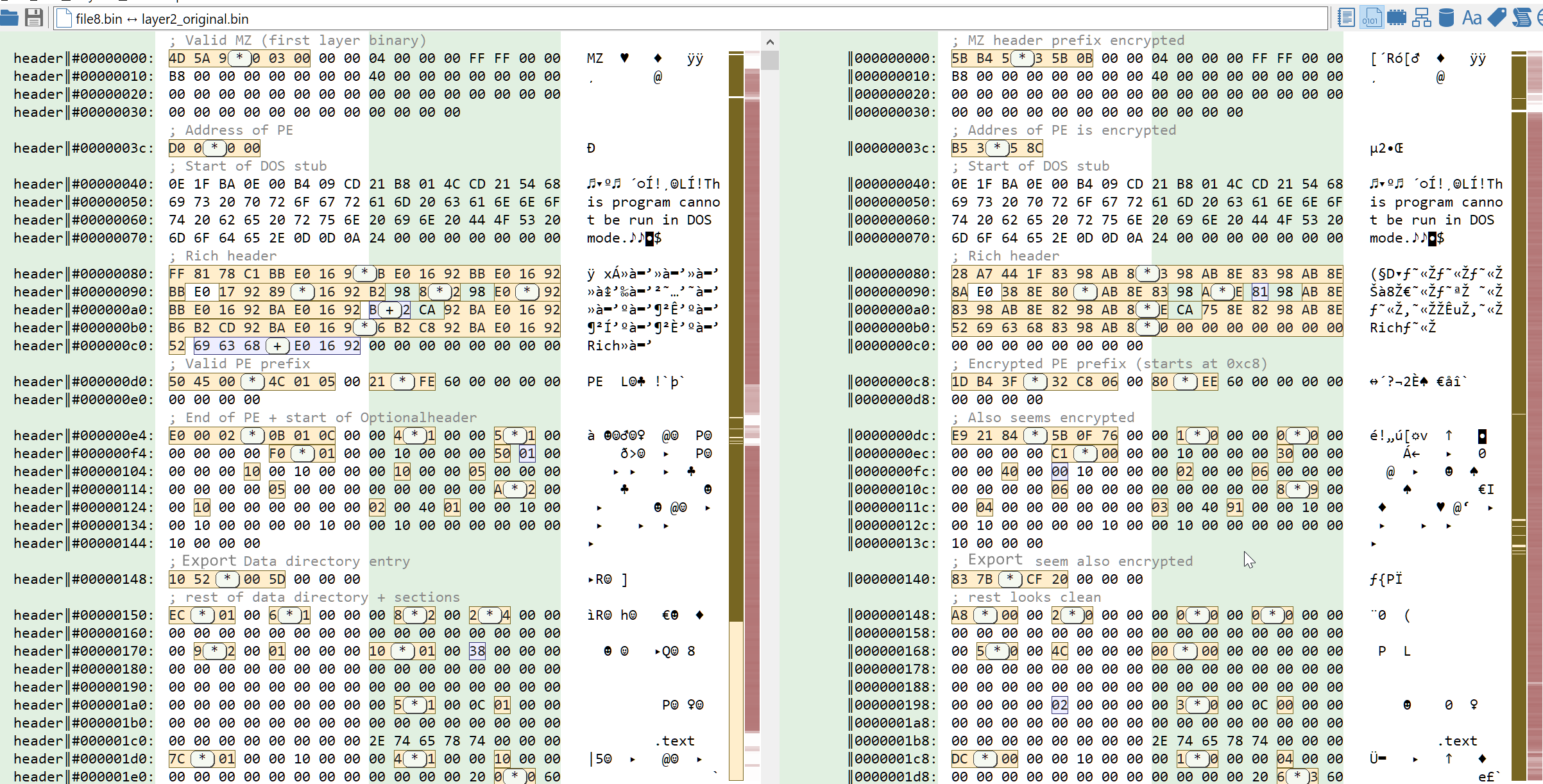

To do this, first dump the decrypted buffer (minus the first 32 bytes which are all zero) into a file. Let's call it layer2_original.bin. Then, select both the first layer (file8.bin) and the buffer (layer2_original.bin) inside your explorer and drag them into Malcat in order to diff them. You can switch between the hex view and the structure view (F2) to see which MZ/PE fields have been encrypted. You should see something like this (minus the comments ofc):

As we can see on the picture, only a few spots in the headers of the decrypted buffer seem to have been encrypted:

- The first 6 bytes of the MZ header:

[#0-#6[ - The last field of the MZ header, AddressOfPEHeader:

[#3c-#40[ - The rich headers are different, but we can safely ignore them

- The first 6 bytes of the PE header:

[#c8-cd[ - End of PE header + start of OptionalHeader, also 6 bytes:

[#dc-#e2[ - Export director entry in the data directory, also 6 bytes:

[#140-#146[

The rest of the differences are all somehow making sense, we are diffing different programs after all. So we will start patching back the obfuscated bytes using our reference program:

- We will copy the first 6 bytes from

file8.bintolayer2.bin - We will patch the AddressOfPEHeader field with the value

0xc8(since the rich header is 8 bytes less than infile8.bin) - We will copy the first 6 bytes of the PE header from

file8.bin[#d0-#d6[tolayer2.bin[#c8-#cd[ - We will copy end of PE header + start of OptionalHeader from

file8.bin[#e4-#ea[tolayer2.bin[#dc-#e2[

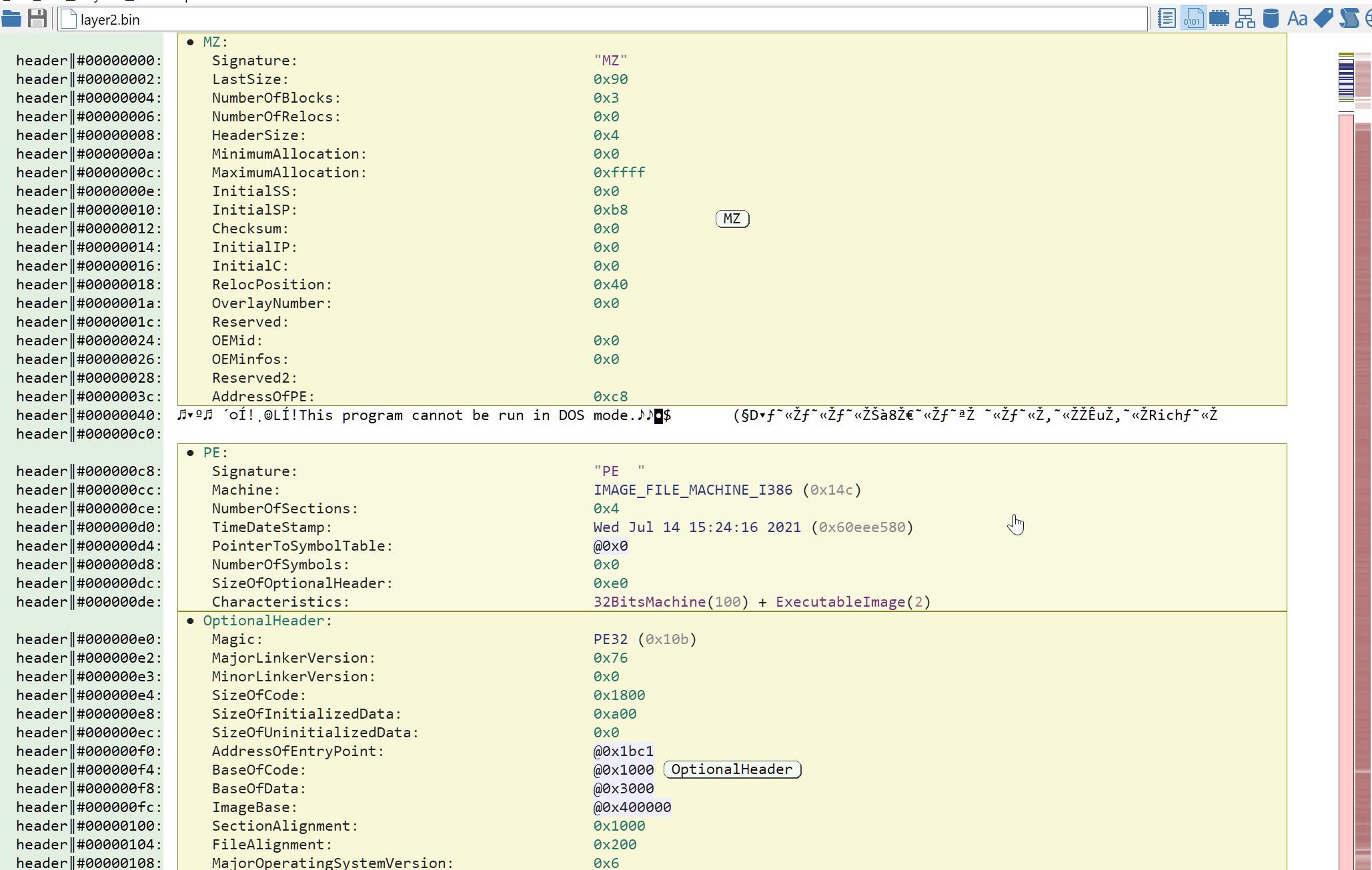

We can safely ignore the obfuscated export directory. Once the patching is done, hit Ctrl+R to reanalyze the patched file and Malcat should now recognize it as a PE file. The headers should then look like in the picture below. For the lazy readers, you can download the patched file here (password: infected).

The second stage

Locating the payload and the decryption function

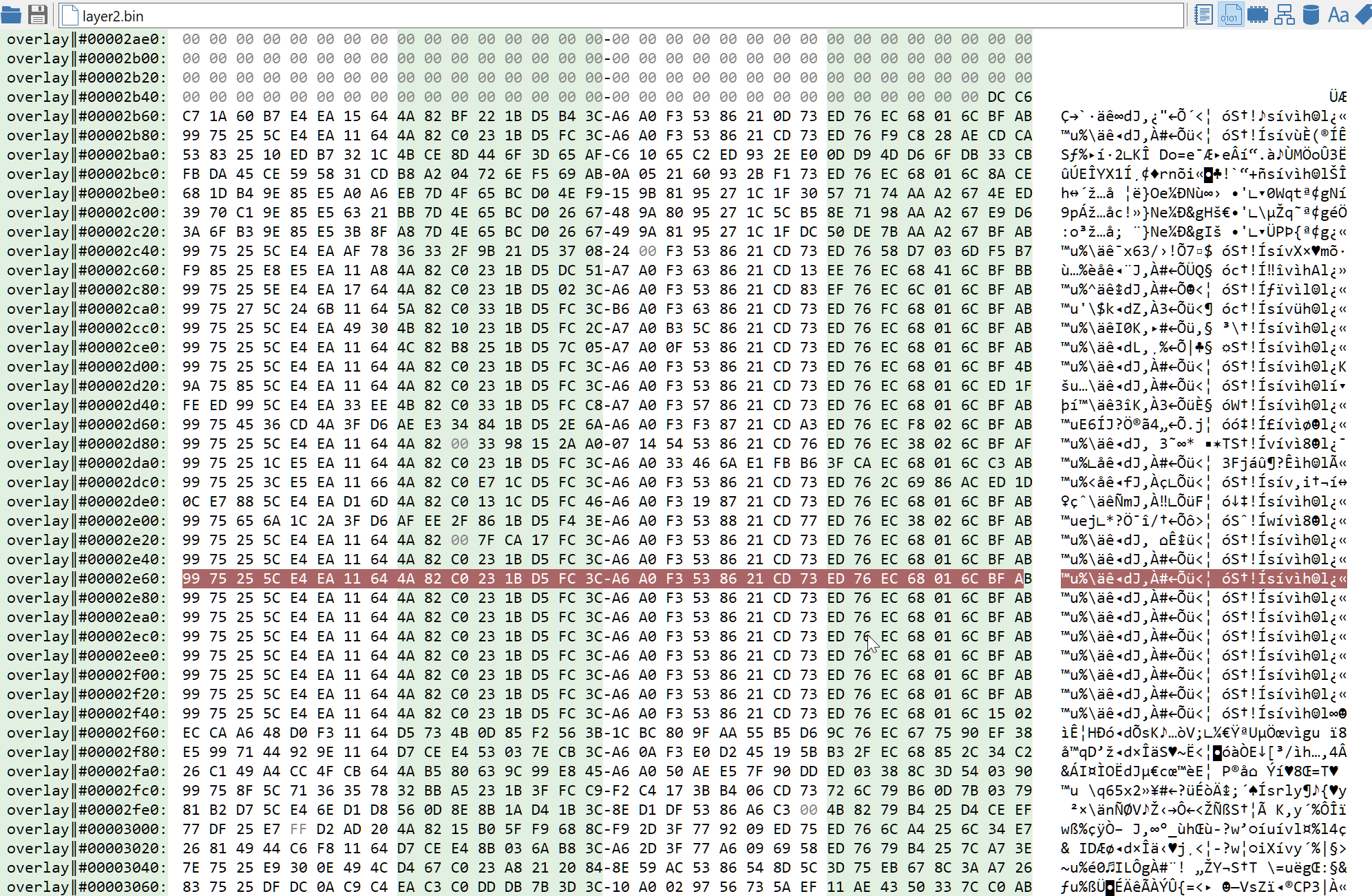

The second layer comes as a tiny PE file with a huge high-entropy overlay. At this stage, since we did not analyse most of the code of the first stage program, it is not clear how the second layer is run. It is possible that the overlay would have been put inside an allocated memory region before running the second stage. But it definitely looks encrypted and thus pretty interesting.

Since the payload is in the overlay (or inside an allocated memory buffer), we can't just look for cross-references like we did in the first stage. We could look for the decryption function inside the .code section, but sadly the code is also obfuscated. Fortunately, by looking at the encrypted data, we can see some 32 bytes long pattern which get repeated a few times. This means two things:

- The payload has been encrypted using a 32 bytes key

- The cipher algorithm is most likely a stream cipher, and a pretty simple one

So instead of looking for references or code, let us look for a 32-bytes long key, i.e a referenced, high-entropy, 32 bytes long, data block. The second stage is quite small, and there is only one data block in the .rdata section which fits this description: [0x40304e-0x40306d[. The key candidate is referenced by a pointer at address 0x404018, which is itself referenced by the very similar functions sub_401301 and sub_401549. Let us have a look at the first one:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | |

This definitely looks like a decryption function, with a key of size 32 (see the uVar3 & 0x1f ?).

Decoding the overlay

The buffer seems to be decrypted by ADDing the key bytes XOR 0xff (aka performing a NOT on the key bytes and then adding the key bytes to the buffer).

There seem to be a twist though. At address 0x40401c we can find an array of 255 dwords, which is a random permutation of the [0 .. 254] interval. This array seems to be used as starting index (uVar3) to decrypt every 255th byte of the buffer. Why would they do that? I don't know, it does not look like obfuscation. It is most likely an anti-dump technique, since some dumpers detect decryption function by looking for sequential writes. This makes sure that the decryption output stream is not written sequentially indeed.

Anyway, we can safely ignore this part of the code since the order of write is irrelevant to us. Let us try to decrypt the buffer using Malcat's transforms. We will first NOT the key, and use the result as key for the add8 algorithm (which is just a add using a repeated key):

And it works, we get a 119808 bytes PE file! But again, parts of the MZ and PE headers seem to be obfuscated :( We won't go through the header reconstruction again, it is the exact same process as for the first stage. Just be careful this time, the Rich header being bigger, the PE header starts at offset 0xe8. You can download the patched file here (password: infected).

The resulting PE is only slightly obfuscated this time. A quick look at Virustotal tells us that this is a Dridex sample. And this time we can be pretty sure that this is the final stage:

- code is less obfuscated (only some constant obfuscation, and strings seem to be encrypted too)

- there is way more code than data, which would be weird for a dropper/injector

- we can see some plain-text constants which make little sense for a dropper, like the ITaskService GUID at address

0x41c960

This is not the main Dridex component though, but the Dridex downloader, since Dridex is a complex multi-stage malware. Decrypting the strings and configuration may be the subject of another article.

Conclusion

We have seen how to navigate inside an Excel document, its sheets and its macros and how to statically extract its payload using Malcat. We also have seen how to circumvent native code obfuscation by ignoring the code and focusing on the data (and using a bit of guessing).

Static unpacking is not reserved to simple malware and can also be used for modern complex families like this Dridex dropper. By focusing on the data instead of the code, we were able to go through the different stages of the dropper with ease and could completely ignore the obfuscation layers.

I hope that you enjoyed this rapid unpacking session. As usual, feel free to share with us your remarks or suggestions!